In today’s consumer-driven economy, the concept of consumer debt has become deeply ingrained in our purchasing habits. But have you ever wondered how this widespread availability of credit affects the prices of the goods and services we buy? This phenomenon, which we call “Debt-A-Sized,” explores how consumer debt has increased prices across various sectors of the economy.

“The easier the financing is, in whatever way, that means that more people can afford to pay more, and that will just bid the price up.” – Richard S. Harris

The Evolution of Consumer Credit

The roots of consumer credit stretch back to ancient civilizations, with evidence of lending practices found in Mesopotamian clay tablets. However, our modern understanding of consumer credit began in colonial times when local general stores kept ledgers of customers’ purchases and payments. This system of “book credit” was born out of necessity due to cash shortages and the seasonal nature of agricultural income.

“Buy now, pay later has always been the way people got their goods in Canada. Colonial settler households were not living independent lives, they were not self sufficient on the farm producing all they needed. They were already getting goods at the general stores and using credit.” – Bettina Liverant

This early form of credit was highly localized and based on personal relationships between merchants and customers. It allowed for flexibility in payments, which was crucial in an era when cash was scarce and incomes were irregular.

As the Industrial Revolution took hold in the 18th and 19th centuries, bringing an abundance of mass-produced consumer goods, a new form of credit emerged: the installment plan. This innovation was partly a response to the need to sell more expensive, durable goods to a broader market.

Companies like Singer Sewing Machines pioneered this approach in the mid-19th century, allowing customers to take home expensive items after making a small down payment and agreeing to regular installments over time. This model quickly spread to other industries, including furniture, farm equipment, and eventually automobiles.

The installment plan represented a significant shift in how people thought about purchases and debt.

“The whole idea that, hey, I can get this today and pay for it tomorrow, well, it’s pretty revolutionary. That’s the first time you’ve got people thinking in a consumer culture that get it today, pay for it tomorrow. And that’s a major psychological shift.” – Ted Michalos

By the 1920s, the installment plan had become widespread, available for a vast array of consumer goods. This expansion of credit coincided with the rise of mass marketing and consumerism, fueling each other in a cycle of increased spending and borrowing.

The Great Depression of the 1930s temporarily slowed the growth of consumer credit, as many families struggled with existing debts, and lenders became more cautious. However, the post-World War II economic boom saw a resurgence and further expansion of consumer credit.

The introduction of the first general-purpose credit card in 1950, the Diners Club card, marked another milestone in the evolution of consumer credit. This was followed by the BankAmericard (later Visa) in 1958 and the Master Charge (later MasterCard) in 1966, which began to transform how people made everyday purchases.

These developments set the stage for the complex, credit-driven consumer economy we know today. From its origins in simple store ledgers to the ubiquitous credit cards and online lending platforms of the 21st century, the evolution of consumer credit has profoundly shaped our economic behavior and the very structure of our markets.

The Automobile Industry: A Case Study in Credit-Driven Pricing

Perhaps no industry better illustrates the impact of consumer credit on pricing than the automotive sector. The story of auto financing is, in many ways, the story of how consumer credit reshaped the American and Canadian economies in the 20th century.

In the early days of automobile production, purchasing a car was a luxury few could afford. With his Model T, Henry Ford aimed to make cars accessible to the average worker. Ford employed a savings plan model where customers would save up for their purchase, often through layaway programs, before taking possession of their vehicle.

“So, call it layaway, call it a savings plan, whatever you want. Henry Ford was selling his cars in the exact same way. So, this doesn’t involve credit of any type.” – Ted Michalos

However, this approach limited sales to those who had to wait and save. General Motors, under the leadership of Alfred P. Sloan, saw an opportunity to expand the market through financing. In 1919, GM revolutionized car buying by introducing the General Motors Acceptance Corporation (GMAC).

GMAC provided financing for both dealerships and consumers, allowing customers to drive away in their new cars after only a down payment. This innovation had a profound effect on both sales and pricing.

“The turn to all of this was when General Motors started selling and delivering the cars in advance of your paying for them. And so now you are actually being granted credit.” – Ted Michalos

This change in financing strategy quickly paid off for GM. The increasing use of credit to fund car prices increased sales. But more than that, the increased demand, fueled by easier access to credit, also allowed manufacturers to raise prices over time.

“GMAC made a car more attainable because of credit. And credit helped General Motors sell more cars.” – Doug Hoyes

The evolution of car financing continued with the introduction of leasing in the 1960s. Leasing allowed consumers to drive more expensive vehicles for lower monthly payments. People perceived leased vehicles to be more affordable because their monthly payments were lower than through a traditional loan.

“The leasing industry really took off in the 1960s as a different form of financing as well and started to compete with the consumer finance companies.” – Mark S. Bonham

The result was once again, more car sales, with more demand further driving up the average price of cars sold.

However, at the end of all those leases, the cars were turned in, leading to a flood of used cars on the market. The resulting drop in residual values at the end of the lease slowed the lease financing market dramatically.

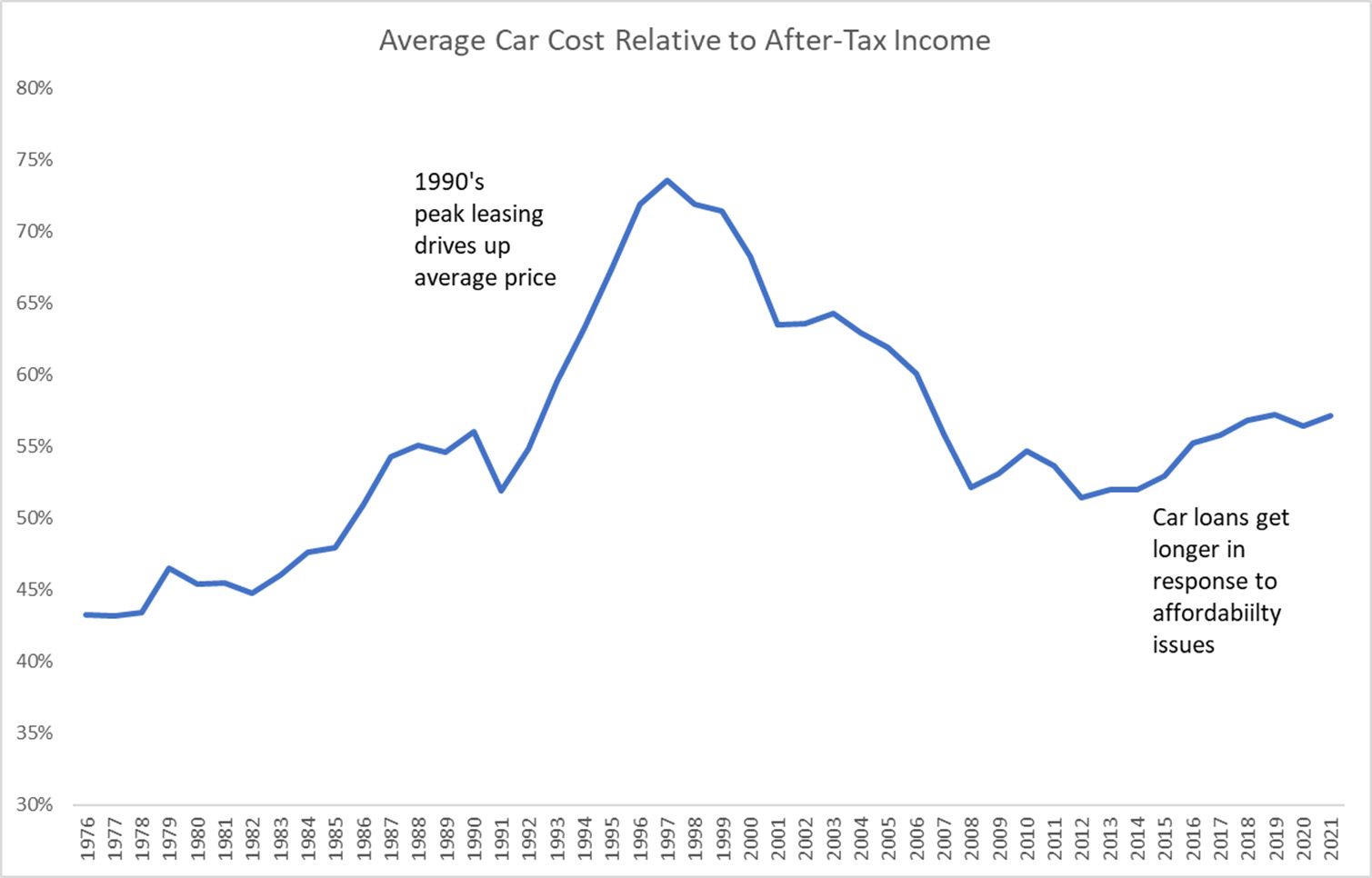

So, without extensive leasing, how could auto manufacturers increase prices? The answer is easy: extend the length of time to pay off a car loan.

In recent decades, we’ve seen the emergence of longer and longer loan terms. Instead of the traditional 3 to 5-year car loans, 6, 7, and even 8-year loans have become common. As of July 2023, J.D. Power reported that 58% of new vehicle loans were 84 months or longer.

Source: Statistics Canada, comparison by Hoyes Michalos

These extended loan terms have allowed consumers to, once again, afford more expensive vehicles, driving up average car prices relative to incomes. This trend has created a cycle where higher prices necessitate longer loans, which in turn enable further price increases.

The auto industry’s embracing of consumer financing has transformed not just how we buy cars but the very nature of car ownership. It’s a prime example of how the availability of credit can reshape an entire industry and consumer behavior along with it.

Housing and Mortgages: How Debt Shaped the Market

The housing market provides one of the clearest and most impactful examples of how debt availability influences prices. The evolution of mortgage lending practices has not only shaped the real estate market but has also had profound effects on the broader economy and society.

In the early 20th century, residential mortgages were rare and very different from what we know today. Typically, they required large down payments of 50% or more, carried high interest rates, and had short terms of 3-5 years with a balloon payment at the end. This meant that homes were unaffordable for the average Canadian, and homeownership was not common.

“Half of the single-family housing in most Canadian cities in the thirties and forties and certainly before then was rental housing.” – Richard S. Harris

The landscape began to change dramatically after World War II. There was an increased demand for housing as veterans returned home and migration to urban centers increased. Governments recognized the need for change and turned to legislative action to help boost housing.

In 1946, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) was formed with the goal of increasing individual homeownership for Canadians. However, CMHC alone couldn’t meet the growing demand for housing and mortgages.

A significant turning point came in 1954 when the Bank Act was changed to allow chartered banks to enter the mortgage lending market.

“There was a shortage of mortgage money at the time. I mean, literally, there were people looking for mortgages who couldn’t get them because the money just wasn’t there. And I think it’s important to remember Canadian banks were not allowed to lend on mortgages until 1954.” – Richard S. Harris

This change, along with CMHC’s introduction of mortgage loan insurance, made mortgages more accessible to average Canadians. It sparked a housing boom that coincided with and fueled the economic boom of the 1950s and 1960s.

Over the following decades, further innovations in mortgage lending continued to make homeownership more accessible – and homes more expensive. The introduction of longer amortization periods allowed for lower monthly payments, making more expensive homes seem affordable.

In 2001, CMHC introduced Canada Mortgage Bonds, which allowed approved financial institutions to pool eligible mortgages into marketable securities they could sell to investors. While the idea was to ensure a supply of low-cost mortgages, it also had the effect of dramatically expanding the mortgage market.

This relationship between mortgage availability and housing prices became particularly evident in the period of ultra-low interest rates from 2009 to 2021. Despite record low rates, housing became less affordable over this period as prices grew faster than the savings from low rates.

“It’s a really interesting question to know to what extend changes in the mortgage arrangements and the opportunities to get mortgages and under what terms, how much that has affected the price of housing.” – Richard S. Harris

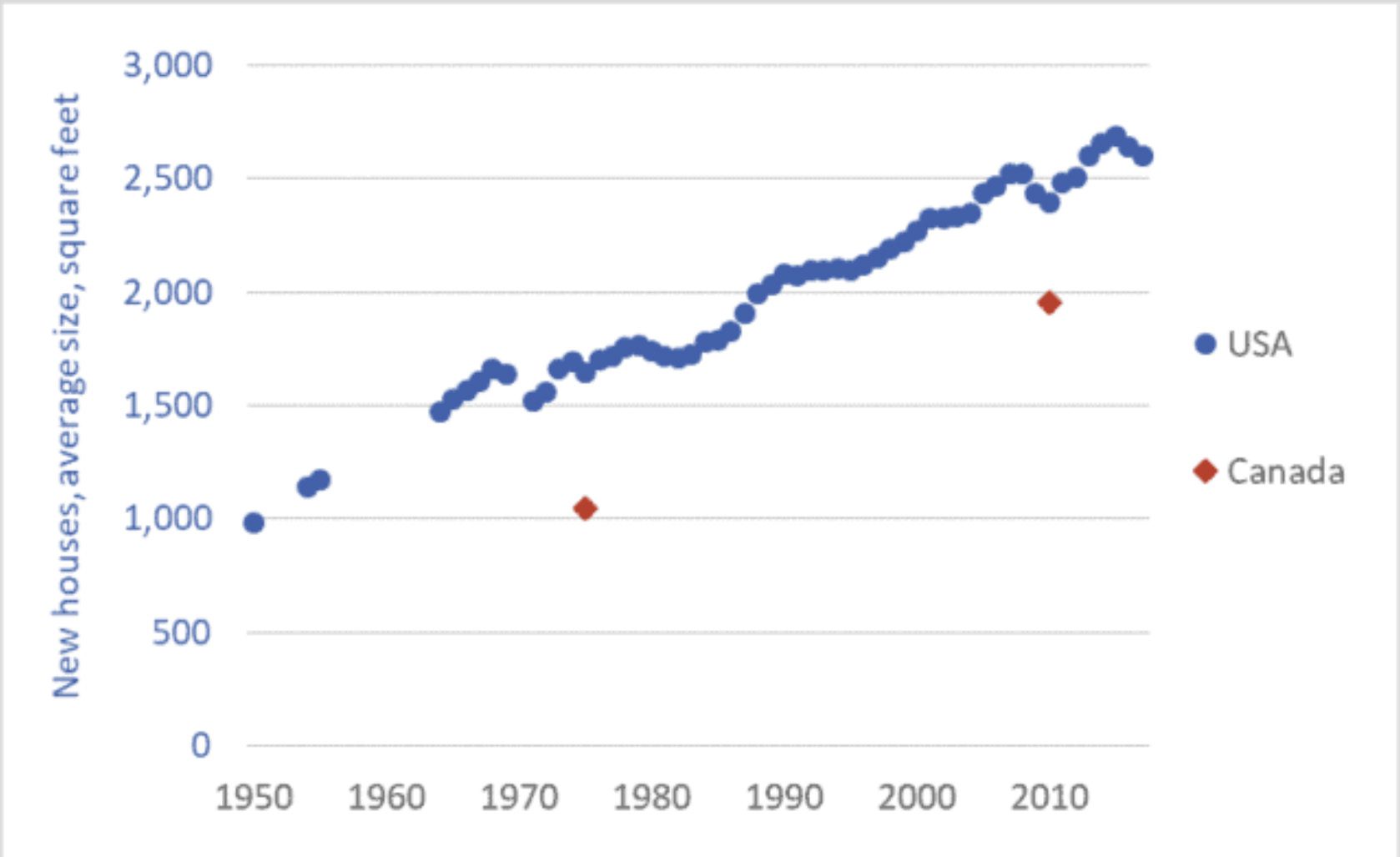

The impact of this easy credit environment was not just on prices but also on the types of homes people bought.

“The other effect is it encourages people to buy bigger homes too because the payments are low. Well, the payments are low because the interest rate was low, is stretched out over a long period of time, longer than normal, longer than we’ve ever historically seen.” – Ron Butler

Average size of new single-family homes, Canada and the US, 1950-2017

Credit: https://www.darrinqualman.com/house-size/

The cycle of easier mortgages leading to higher prices has created challenges for future generations of homebuyers. It has also increased household debt levels and potentially increased economic vulnerability to interest rate changes or economic downturns.

The housing market clearly demonstrates how the availability of credit can reshape prices. By making it easier to borrow larger sums over longer periods, mortgage innovations have enabled a long-term trend of housing prices growing faster than incomes. This “Debt-A-Sized” effect in housing has far-reaching implications, influencing everything from individual homeownership to political policy.

Education and Student Loans: The Debt-Price Connection

The realm of higher education provides yet another example of how increased debt availability can drive up prices. The history of student loans and their impact on tuition costs is a relatively recent phenomenon but one that has had profound effects on both education and the broader economy.

Government student loan assistance has been available in Canada in one form or another since 1939, but initial programs reached very few students. The landscape began to change dramatically in the 1960s, coinciding with the post-war baby boomers reaching college age and a surge in post-secondary enrollment.

In 1964, the Canada Student Loans Program was formed. This program allowed a growing number of students to take out loans from private financial institutions, with payment guarantees backed by the federal government. The goal was to make higher education more accessible to a broader range of Canadians.

While student loan programs did indeed make education more accessible, they also had an unintended consequence: they enabled universities to raise tuition without reducing enrollment. This created a cycle where higher tuition led to larger loans, which in turn allowed for further tuition increases.

The introduction of tax-sheltered Registered Education Savings Plans (RESPs) in 1972 was intended to encourage families to save for education, potentially reducing reliance on loans. However, despite this initiative, over 40% of post-secondary students continue to finance their education with debt.

In recent years, we’ve seen a significant increase in both tuition costs and student debt loads. The long-term consequences of this cycle are significant. Not only has it led to higher education costs, but it has also saddled many graduates with substantial debt, affecting their financial decisions for years after graduation. This debt burden can delay major life milestones such as homeownership, starting a family, or saving for retirement.

The student loan system, while well-intentioned, has become another example of how increased access to credit can lead to price inflation, creating a cycle of debt that extends well beyond graduation day. It’s a stark illustration of the “Debt-A-Sized” phenomenon in action, showing how even sectors like education are not immune to the price-inflating effects of readily available credit.

The Role of Credit Bureaus and Credit Scores

The evolution of consumer lending from relationship-based decisions to algorithmic credit scoring has played a crucial role in the expansion of consumer debt.

Initially, the availability of credit was based on having a good relationship with your banker. That worked well when few consumers were borrowing. However, the increase in consumer credit led to a need for more and better lending policies and credit approval processes.

“If all your customers pay you every month your credit policies are too tight, you want to give them more credit so you can get them to buy more. Eventually, somebody is going to stop paying. If you’ve got more than one out of every on hundred defaulting on their payments, then your credit policies are too loose and you’re losing money.” – Ted Michalos

The history of credit reporting in North America dates back to the mid-19th century when small, local credit bureaus began collecting information on consumers’ creditworthiness.

Initially, these early credit reports were simple records of an individual’s earnings and their ability to keep up with payments. The information was often kept on paper in large filing cabinets, and reports didn’t include a numerical credit score. Instead, they relied on narrative descriptions of a person’s credit history.

As consumer credit expanded in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, retailers and credit managers needed a more efficient way to determine who was likely to repay a loan. This led to the growth of credit reporting as an industry.

The 1960s marked a significant turning point for credit reporting. Many local bureaus were consolidated into larger national organizations. The advent of computers allowed for the digitization of credit records, making it easier to collect, store, and distribute credit information.

In Canada, the industry eventually consolidated into two major credit bureaus: Equifax and TransUnion. Each developed their own proprietary credit scoring models.

The introduction of credit scores in the late 1980s and their widespread adoption in the 1990s fundamentally changed lending practices. These scores allowed for faster credit decisions and the expansion of lending to a broader population.

“In 1989, is essentially when they introduced the FICO score, so the scoring system for the credit reporting agencies, here in Canada. The Fair Isaac Company or Corporation now, I guess, is the name of the big one. But it didn’t really start taking effect or gaining traction until later in the nineties.” – Richard Moxley

However, the focus on credit scores has also led to what some experts call “credit score obsession” among consumers. By the early 2000s, credit bureaus began offering credit report services directly to consumers for a monthly fee. This was billed as credit monitoring and identity theft prevention, but it had the unintended consequence of making many consumers fixated on their credit scores.

Apps and services offering free credit scores have proliferated, often with the goal of promoting credit products to users.

“If you think about Borrowell, Credit Karma, or any of the other third-party apps… They make money by essentially advertising… Anytime you click on any of their advertisements, they get a piece of that and that’s how they make money.” – Richard Moxley

This obsession with credit scores has created a new dynamic in the consumer credit market. Many people now actively work to improve their credit scores, sometimes taking on additional credit to do so. While this can lead to more responsible credit use, it can also encourage people to take on more debt than they might otherwise.

“It’s one of those things where when the system is so complicated that most people don’t even know how to read their credit reports. So, we’re so obsessed with that three-digit number because it’s the only thing that most consumers would understand about their credit report. The higher it is, the better.” – Richard Moxley

The credit bureaus themselves have benefited significantly from this shift. They make money not just from selling reports to lenders but also from selling services directly to consumers.

This focus on credit scores has become another factor in our story of becoming “debt-a-sized.” By making credit more accessible and encouraging consumers to focus on their creditworthiness, credit bureaus have played a significant role in expanding consumer debt and, indirectly, in driving up prices across various sectors of the economy.

The Cycle of Debt and Pricing

The relationship between debt availability and pricing creates a self-reinforcing cycle. Easier access to credit allows consumers to spend more, which drives up prices. Higher prices, in turn, necessitate more borrowing for purchases.

This cycle is particularly evident in big-ticket items like homes and cars, where the focus has shifted from the total price to the monthly payment.

“It’s not what the something costs anymore; it’s can I afford the payments, and the advertising is focused on that now too. You can pay this weekly or biweekly! It’s a manageable amount.” – Ted Michalos

The broader economic implications of this cycle are significant. While increased consumer spending can drive economic growth, it also leaves households more vulnerable to economic shocks and can contribute to financial instability.

The “Debt-A-Sized” phenomenon has profoundly shaped our economy and society. From cars to homes to education, the availability of consumer credit has consistently driven up prices, often outpacing income growth.

“Society as a whole benefits by loose credit policy because you’re maximizing not only the return of the money, but you’re maximizing consumption, which means you’re maximizing output. Everybody’s got jobs, everything. Rising tides raise all boats. But when you look at individual households, the risk is that if anything goes wrong, any kind of interruption in the income stream, you’re in a lot of trouble.” – Ted Michalos

Understanding this relationship is crucial for consumers navigating today’s credit-driven marketplace. While credit can provide valuable opportunities and flexibility, it’s important to consider the long-term costs and risks associated with debt-fueled consumption.

“Every dime that you spend, that you don’t actually have the money to pay for, is putting the burden on your future self.” – Joel Sandwith

As we look to the future, new forms of consumer credit continue to emerge, from “Buy Now, Pay Later” services to cryptocurrency-based lending. While these innovations may offer new opportunities, they also have the potential to further fuel the cycle of debt and price inflation.

Ultimately, breaking or mitigating this cycle may require a combination of policy changes, financial education, and a shift in consumer attitudes towards debt and consumption. But can we?

“Our entire economy is based on debt.” – Doug Hoyes

“Credit is responsible for the acceleration of consumerism.” – Ted Michalos

By understanding the “Debt-A-Sized” phenomenon, we can make more informed decisions about our personal finances and advocate for systemic changes that promote true affordability and financial stability.

“Credit can be a useful tool if it is used wisely. The problem we have, of course, is that we use too much credit, and that is what causes problems.” – Doug Hoyes

Watch the full documentary on YouTube by Hoyes Michalos and Debt Free in 30