Ice cream is seasonal. Fruit is seasonal. Boating – certainly seasonal. Housing can be seasonal.

But insolvency filings?

Yes – they really are quite seasonal too.

Consumer insolvencies are also subject to cyclicality, secularity, and of course the vagaries of markets, downturns, recessions and the like. The macro stuff. Let’s examine how all this works.

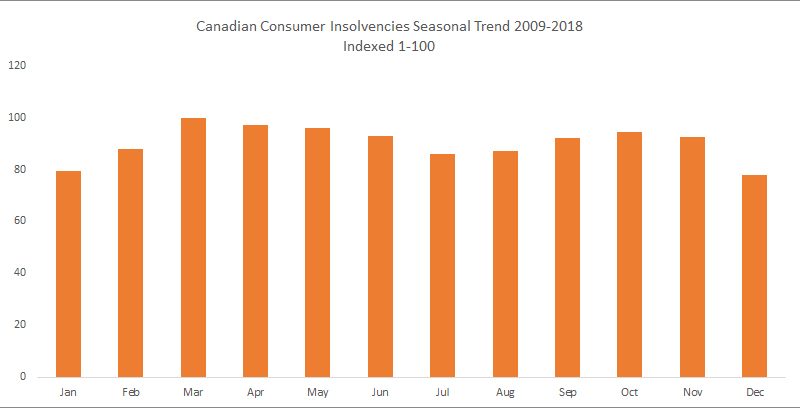

Insolvency Seasonality

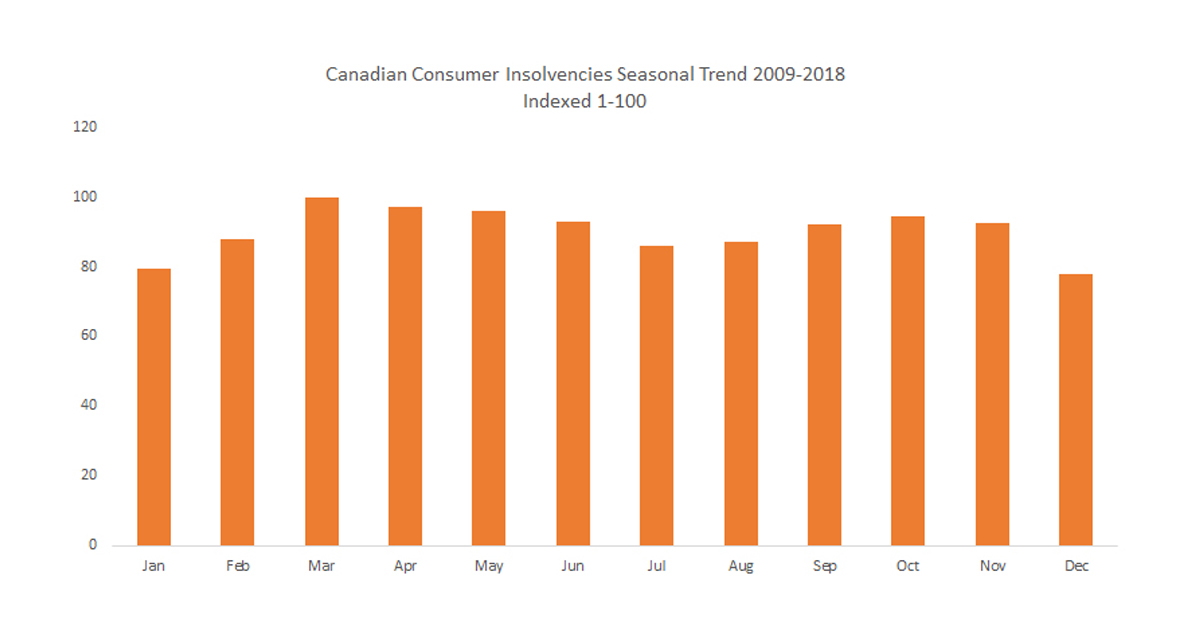

People are usually surprised to hear how very seasonal things are in the insolvency world. If I tell somebody “It’s winter (or fall), so we’re pretty crazy right now at work” I get a strange look. After all we don’t have a deadline like filing your taxes so you’d be reasonable to expect that insolvencies would be evenly spread through the year. I think people figure that a significant financial undertaking like filing a legal insolvency (a personal bankruptcy or a consumer proposal) takes planning – perhaps not meticulous, but certainly with some thought and intention as opposed to reaction.

But what frequently drives people to see an insolvency professional is much more down to a triggering event or a final capitulation. Faced with a wall of debt, and tired of constantly juggling multiple due dates for bills and credit minimum payments, people cave.

Beyond being technically insolvent (owing more than they can repay) someone needs to be ready both emotionally and intellectually to file and the very nature of how we manage our lives through the year has a big impact on when people choose to act. The result is that the seasonality of insolvency follows, with some lag, our patterns of spending and behaviour during a typical 12-month period.

Let’s look at a typical year.

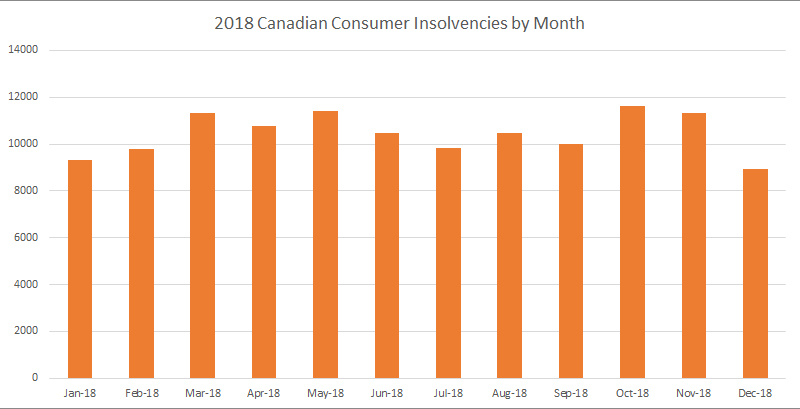

January

It’s post-Christmas; you just spent the most money you’re likely to spend all year on gifts and non-essential items. Now is the reckoning – you get your credit card bills sometime in mid-late January and the realization hits you. Many people blow their last remaining credit at Christmas, buying a little happiness despite worrying they will never have a chance to pay their debts off in full. Now the post-holiday debt hangover begins.

February to May

This is the annual period of increasing intensity of insolvency filings. It starts in late January really, and continues as people realize the financial straits they face. The lengthy deliberations are well past – the soul-searching is long done. They now need to act based on sheer balances and interest rates alone. It’s math now. It’s down to the “Estimated Time to Pay” wording on the monthly statement.

A lot of this is also psychology – winter is a time for brooding. We’re holed up indoors, thinking about our problems. Mulling. Deciding.

The peak generally happens in late April to May. Even the spring weather has an impact. A rainy week means more phone calls. A sunny week means they’ll try to kick the can down the road a little longer.

June

Things start to normalize as kids finish school, vacation plans start to materialize, and the Canadian predilection for enjoying the brief summer living sets in. We’ll worry about finances later. Filings in June tend to reflect those who’ve largely already started the process. New calls into our offices have already slowed.

July & August

The summer is our quiet period. People are busy getting INTO financial trouble, not out of it. Only the people who are in REAL trouble and must file due to the scale of their financial disaster tend to file during the summer.

September to November

The fall reflects the second ‘busy’ period for licensed insolvency trustees. School has begun again, routines are back, and reality bears down. It’s time to take a hard look at where we’re at and what we’ve done. Normally insolvency filings in this period are high. Canadians go inside more again, returning to brooding & introspection. They buckle under the weight of their debt and seek help.

December

Our only real ‘quiet’ period is December, and mostly late December at that. People are, of course, busy spending and trying to celebrate in the lead-up to Christmas. Thoughts of debt repair and such prosaic notions are far from one’s sugar-plum infested mind. We’re getting INTO trouble again or, at the very minimum, hiding for a little longer.

The odd part of December is that we do a lot of bankruptcy filings, at least at Hoyes, Michalos. Timing can matter if you are deciding when to file bankruptcy as we reach year end. If someone does contact us in December, we alert our clients to the fact that if they file in December (vs January), Canadian insolvency law means they stand to lose potentially only one tax refund instead of two. Trustees are obliged by the Bankruptcy & Insolvency Act to file a bankrupt’s tax returns for the year of their filing. Any refund in said year, and all previous years, is an asset of the estate and is the trustee’s for distribution to the creditors. So, file in December: you are only subject to one tax refund seizure. File in January and you lose two refunds. This incentivizes people to get bankruptcies filed before January. It’s important to note that this is not applicable to consumer proposals in which assets, including tax refunds, do not vest in the trustee.

But what if you owe taxes to the CRA instead? In this case it’s usually good to wait until January to file a proposal as then you can include your entire previous tax year’s arrears owing (and all previous years) without adding a special clause in your proposal allowing you to also include the new year’s tax debts.

The Insolvency ‘Cycle’

Now let’s switch to the more macro-economic factors. Where are we at in the broader insolvency cycle?

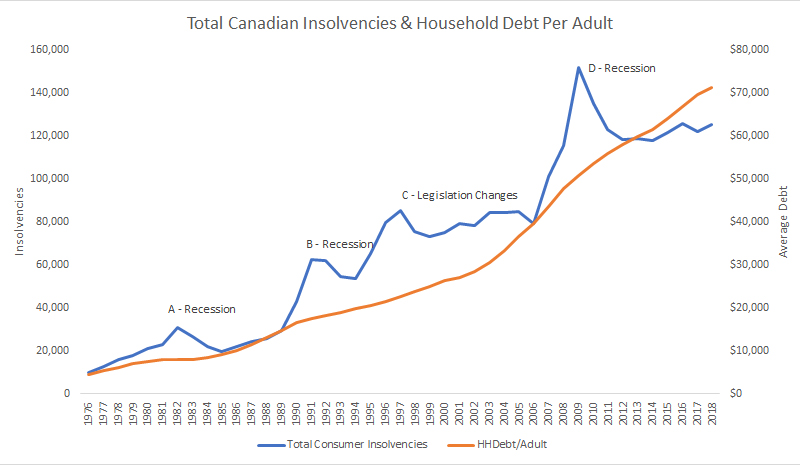

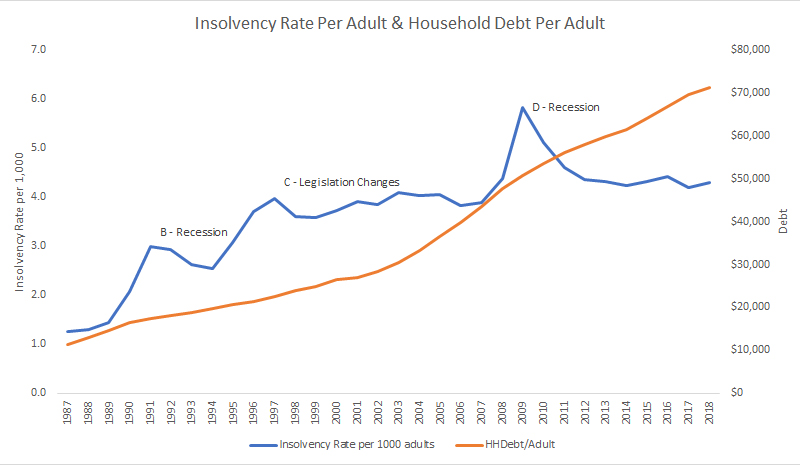

There is seasonality, but there is also a definite cyclicality to consumer insolvencies. Insolvency trends are largely dependent on two broader cycles: the economic cycle and, much more importantly, the consumer credit cycle.

The last insolvency peak in Canada followed the global recession of 2009 when 148,378 Canadians filed insolvency. While there is some short-term correlation between recessionary periods and insolvency peaks there is a lot of lag time. Sure, more people may be driven toward that last resort by job losses that happens before and during a recession, but there is lag time between when a person gets into serious financial trouble and when they eventually file an insolvency (12-24 months, usually). Insolvencies tend to peak after the recovery has already started. It’s the debt people accumulated while off work that creates the problem that needs to be solved once they return to work. Or, if they carried debt pre-recession, a reduction in household income due to job loss can become the last straw.

Canadian Insolvency Cycle – Broader Economic Factors Affecting Peak Insolvency Periods

1980 – recession (Jan-Jun)

1981-1982 – recession (Jun 1981-Oct 1982)

1990-1992 – recession (March 1990-April 1992)

1992 – Consumer Proposal provisions added

1997 – 10-year limitation on student loan discharge added, causing spike in student loan bankruptcies

2008-2009 – recession (Oct 2008-May 2009)

2008 – student loan limit reduced to 7 years

2009 – Consumer Proposal limit increased to $250,000

2015 – Oil downturn

Following the global recession, Canadian consumer insolvencies dropped off rapidly reaching a post-recession low of 118,050 in 2014. Even the slight rise in 2015-2016 was more regional than national reflecting the boom and bust of oil-dependent economies. Ontario insolvencies continued to decline during this period. Think of this as ‘secular market’ forces (and kudos to our recent podcast guest Danielle Park of Juggling Dynamite fame, who brought this concept or term up when she and I were chatting in my office briefly). Smaller, localized, mini-recessionary impacts.

However, while recessions create peaks they still don’t explain the longer term direction of insolvency growth in Canada. Before the 2009 recession, Canadian insolvencies generally trended upward in line with rising consumer credit levels, with peaks and valleys occurring between economic cycles. Smaller trends caused by changing bankruptcy legislation, changes in interest rates and regional market conditions created marginal swings, but overall the level of insolvencies in Canada rose as consumers took on more credit.

Which brings us to the credit cycle and what’s happening today.

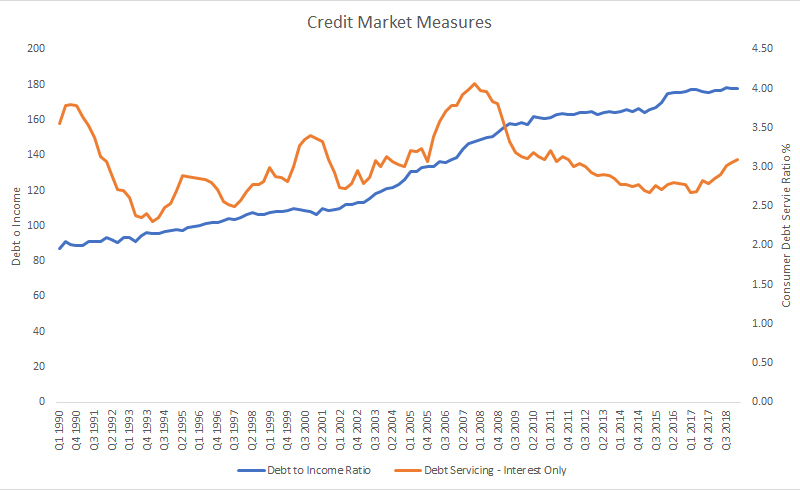

Consumers traditionally run up their credit over the course of a few years and this accelerates when banks are in a mood to lend. Times are good? Bank’s relax credit. Low interest rates plus a steaming hot housing market? Consumers demand access to more credit – both secured and unsecured.

The last several years have certainly qualified as ‘good times’ in Canada when it came to consumer debt. When credit flows and rates are low, people became accustomed to having debt. The outlook for the future is good, so our debt brains relax. The warning bells subside. Our System 1 brain is in control; System 2 is napping in the background.

Consumer credit growth blossomed, as did mortgage debt. Commonly rolled-out measures such as the debt-to-income ratio rose steadily.

What is notable is that, since around 2011, the relationship between rising household credit levels and consumer insolvency rates per capita seems to have broken, or at least stalled.

In the past, the individual cycle of carrying high debt levels usually breaks, with or without broad economic triggers. Credit builds up, and after a few years many consumers become overextended. A personal event – be it a job loss, divorce, illness, emergency expense – triggers insolvency. The individual debtor cannot handle their debt loads any longer so they file a bankruptcy or consumer proposal. A natural personal financial reckoning, so to speak, which fed the longer-term rise in consumer insolvencies in Canada.

But the period following the last recession has been anything but normal economically in Canada. Record-low interest rates combined with robust housing gains have allow people many different avenues by which to avoid filing insolvency. They’ve chosen instead to shift credit to lower rate vehicles like lines of credit, take out longer-term car loans and roll old debt into new. Homeowners have embraced the use of HELOCs, and debt consolidation has become a massive industry supported by a broader array of willing lenders. We see this in the monitoring of our Homeowner’s Bankruptcy Index which has dropped from record highs of almost 35% in 2011 to the 5-7% range in early 2019. In recent years, Canadians have proven incredibly resourceful at shifting their debt around, in effect kicking the problem down the road.

As a result, the insolvency industry has gone several years beyond what would otherwise be expected to be a natural systemic purge.

So what does that mean necessarily?

Based on what I’ve seen in my 11 years in this field, a long run-up of free credit will eventually cause more consumers to hit their own personal wall. What matters is what is close to home.

Recently, filings are very much on the rise. Even Ontario is starting to see cracks in our ability to maintain all this debt with consumer insolvencies up in 2018, after 8 years of consecutive declines. And 2019 looks to bring double digit growth to Ontario insolvency filings if current trends continue.

And this time, there is a whole lot more consumer debt in the system that has built up during the good times. Does this mean that the next (current?) insolvency filing tide will be much higher? I tend to think so, for several reasons.

One, there is a pent-up consumer debt bubble that didn’t really have a full reckoning in a normalized debt cycle a few years ago. The credit ride was free, and people rode it. They didn’t shed their debt, they binged on it.

Two, almost every study shows very little savings in the hands of Canadians. They have no cushion, no room to maneuver. Many are a paycheque away from serious financial trouble (not insolvency, as that takes a significant lag time but trouble from which it will be hard to extricate themselves.)

Three, much of the asset base is illiquid. Tough to just up and sell your home in an expensive housing market, because you still need to live somewhere. And the mentality is: if you sell, good luck getting back in. It’s the FOGO more than the FOMO. And you can almost feel the collective shudder amongst heavily leveraged homeowners at the inkling that housing prices could fall.

Four, young people are in deep. They are now the fastest-growing debt accumulators and insolvency filers. Our ‘next generation’ is behind the 8-ball financially. And with the student loan burden getting worse, it’s not a stretch to think many Canadians entering their 40’s – which would traditionally be the start of their highest-earning years – will be making ends meet for a decade or so with underemployment rampant. And along with that debt comfort comes a greater willingness to file a proposal in order to address the problem. We find that despite a greater obsession with credit scores and that system, younger people are more willing to engage the services of a trustee to get a financial fresh start.

All in all, I believe the credit correction is inevitable and it’s not a good scenario for a gentle landing.

Source:

- Office of the Superintendent of Bankruptcy Canada: Insolvency Statistics

- Statistics Canada: Table: 11-10-0137-01 (formerly CANSIM 177-0001)

- Statistics Canada: Table 10-10-0118-01 Credit measures, Bank of Canada (x 1,000,000);

- Statistics Canada: Table 17-10-0005-01 Population estimates on July 1st, by age and sex;

- Statistics Canada. Table 38-10-0238-01 Household sector credit market summary table, seasonally adjusted estimates