The Bank of Canada has raised its central bank rate eight times so far since last year reaching 4.50% in January 2023, up from a low of 0.25% at the beginning of 2022. The resulting higher cost of borrowing has led to a significant decline in mortgage originations and housing prices and plenty of discussion about a recession in Canada.

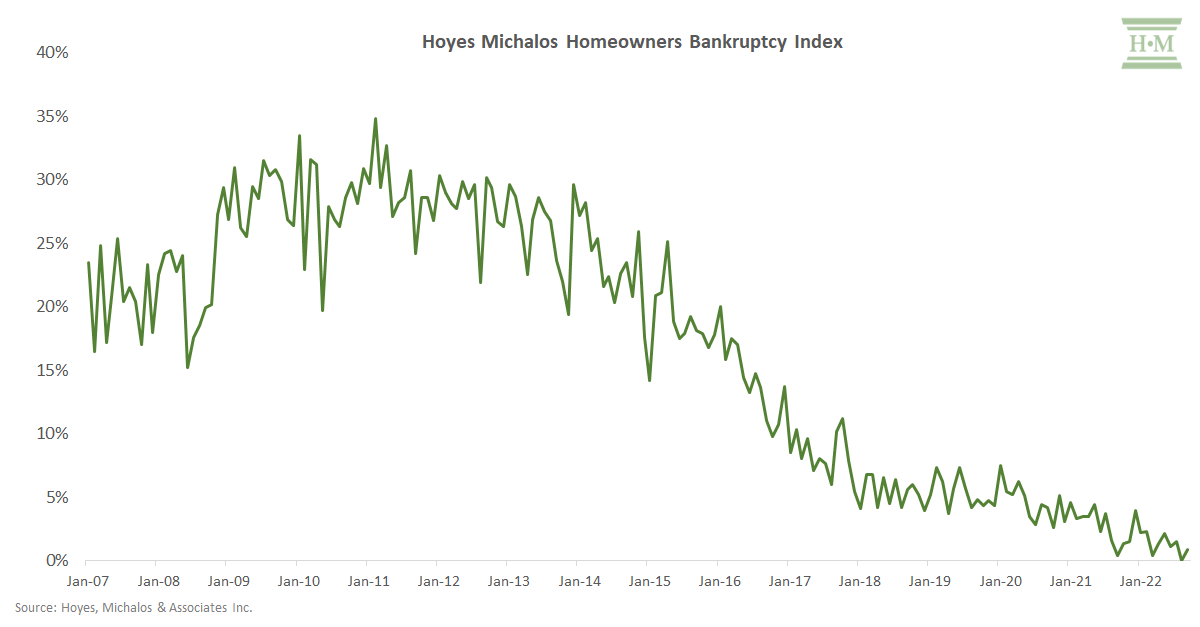

Yet despite rising interest rates, particularly mortgage rates, homeowners are still not filing insolvency (either a bankruptcy or consumer proposal). In fact, our Hoyes Michalos Homeowners Bankruptcy Index (HBI) was 2.0% in December 2022.

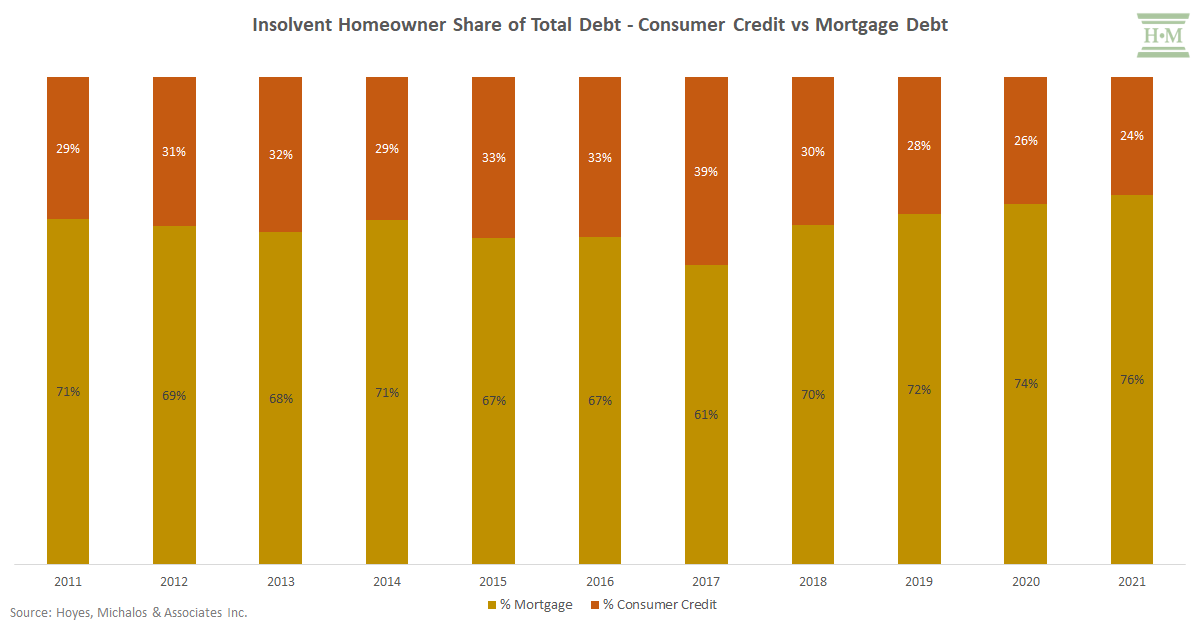

To understand what triggers a homeowner to file insolvency rather than refinance, let’s look at some historical data. In 2011, when our HBI was at its peak, 29% of an insolvent debtor’s total household debt was consumer credit and 71% was mortgage debt.

For the next few years, it was rising consumer credit that was driving homeowner insolvencies, not necessarily unaffordable mortgages. By 2017, consumer credit as a percentage of total debt for insolvent homeowners had risen to 39% of their total debt.

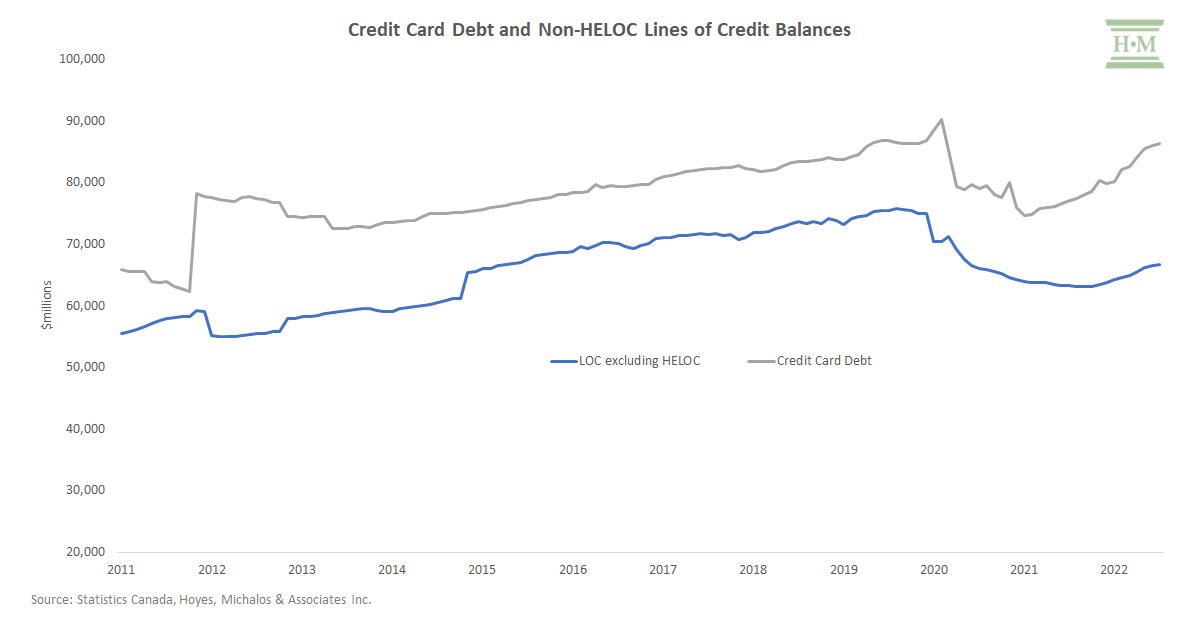

Two of the biggest drivers were rising credit card debt and unsecured lines of credit.

A homeowner heavily indebted with consumer credit reaches a wall eventually. To restructure high unsecured debt balances, homeowners have two primary options, refinance or file a consumer proposal.

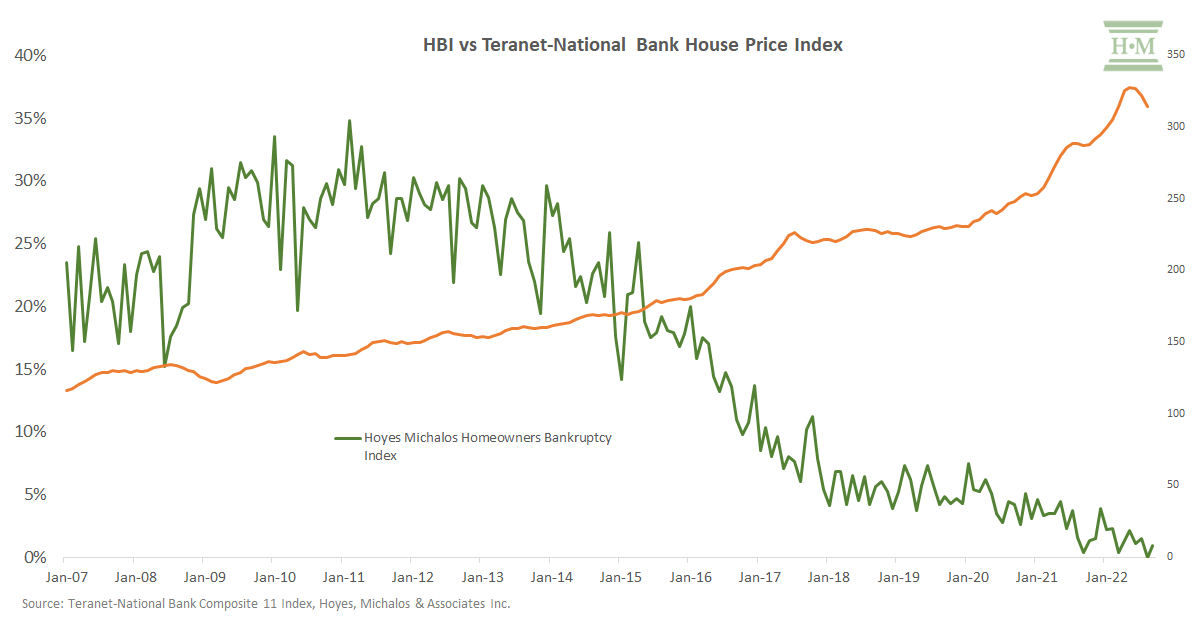

In recent years, few homeowners were filing insolvency despite rising consumer credit due to two factors: low interest rates and rising home prices. These economic conditions allowed more Canadians to consolidate unsecured debt through their home equity. Suddenly, their budget became balanced again, mostly due to mortgage refinancing.

In recent years, however, those few homeowners filing a consumer proposal or bankruptcy are doing so due to heavy mortgage debt. In 2021, when our HBI was only 2.80%, mortgage debt accounted for 76% of the average insolvent homeowner’s total household debt, the highest we’ve seen since starting our study in 2011. These were homeowners with large high-ratio mortgages who had no credit capacity to refinance.

OK, so if high mortgage debt is driving insolvencies, let’s get back to why we don’t think we will see a sudden uptick in homeowner insolvencies.

The truth is, we do not expect a significant rise in homeowner insolvencies until mid- to late-2023. Why? Because there is a significant time lag between when interest rates rise and when the resulting costs become financially unbearable.

First, payments won’t rise immediately for most. Homeowners with a fixed mortgage rate will not see their mortgage payments rise until their mortgage comes up for renewal. Variable payment holders may also have a static payment, and while many are reaching their trigger rate, some will extend their amortization by putting little, or nothing, towards equity so they can keep their monthly mortgage payment manageable for as long as possible.

Second, history shows us that homeowners will do anything and everything to keep up with their monthly mortgage payment, including borrow more. And homeowners in 2022 have more ability to withstand interest rate shocks than they did pre-pandemic.

The reason lies once again in credit capacity and much of what happened during the pandemic to consumer credit. Both credit card balances and outstanding non-mortgage lines of credit fell dramatically in 2020 and most of 2021 as Canadians, including homeowners, paid down credit balances. This trend is reversing, with credit card and lines of credit balances increasing again however they are not yet as high as they were pre-pandemic.

And here’s the thing. While people paid down balances, it is unlikely many cancelled or lowered their credit limits. This provides a lot of credit room to weather rising mortgage and debt payments. However, eventually a budget crunch will happen. Homeowners will once again max out unsecured credit borrowing and that is when we will begin to see a rise in homeowners filing consumer proposals again.

Even for those facing rising mortgage rates today as their variable rate mortgage reaches a trigger, the banks are provided additional credit capacity to weather the storm. While most maximum amortization periods are 25 years for insured mortgages and 35 to 40 years for non-insured mortgages, most lenders are currently allowing borrowers to make interest only payments, or principal payments of just 1 dollar, extending the amortization almost as much as need to accommodate, at least for now.

In summary, it will take a while before homeowners’ crumble under the weight of their mortgage payments. However, the longer rates remain high and the more likely we see a rise in unemployment as a result, the sooner the tide will turn.